The music of Charles Christopher Parker—as well as the music of many other musicians—probably has the greatest influence on my own music. I view Parker as a major composer, albeit primarily a spontaneous composer. His written compositions, similar to many other very strong spontaneous composers, were mainly jumping-off points for his spontaneous discussions. Parker was also someone whose function would be analogous to the role of a master drummer in traditional West African societies. For me, Parker translated these combined ideas, via a style that is a sophisticated version of the Blues, into something that can express life, from the point of view of the African-American experience in the 20th century. Many others, John Coltrane for example, contributed to the expression of this transitional music on a technical, intellectual and spiritual level. |

|

Die Musik von Charles Christopher Parker – wie auch die Musik vieler anderer Musiker – hat vielleicht den größten Einfluss auf meine Musik. Ich betrachte Parker als einen bedeutenden Komponisten, wenn auch hauptsächlich als einen spontanen Komponisten. Seine geschriebenen Kompositionen waren – ähnlich wie die vieler anderer sehr starker spontaner Komponisten – hauptsächlich Absprungstellen für seine spontanen Diskussionen. Parker war auch einer, dessen Funktion mit der Rolle eines Meister-Trommlers in traditionellen west-afrikanischen Gesellschaften vergleichbar war. Für mich übersetzte Parker diese gemeinsamen Ideen durch einen Stil, der eine verfeinerte Version des Blues ist, in etwas, das das Leben ausdrücken kann – aus dem Blickwinkel der afro-amerikanischen Erfahrung im 20. Jahrhundert. Viele andere, zum Beispiel John Coltrane, trugen zum Ausdruck dieser traditionellen Musik auf einer technischen, intellektuellen und spirituellen Ebene bei. |

I get a lot of what I call micro-information from Parker. There is much in the way of technical things such as melodic movements and progressions, etc., but there are also the linguistic aspects of Parker’s music and the emotional and spiritual content. In studying the history of how this music was developed, one can glean a great deal of insight about the natural world as well as human nature in general. This story has been told many times before; the clothes may be different, but it is the same story. |

|

Ich erhielt von Parker eine Menge von dem, was ich Mikro-Information nenne. Viel betrifft technische Dinge, wie melodische Bewegungen und Progressionen usw., aber auch die linguistischen Aspekte von Parkers Musik und den emotionalen und spirituellen Inhalt. Durch das Studium der Geschichte, wie diese Musik entwickelt wurde, kann man eine große Menge an Einsichten sammeln, sowohl über die natürliche Welt als auch über die menschliche Wesensart im Allgemeinen. Diese Geschichte wurde schon früher oft erzählt. Die Kleider mögen unterschiedlich sein, aber es ist dieselbe Geschichte. |

In my opinion, by far the most dramatic feature of Bird’s musical language is the rhythmic aspect, in particular his phrasing and timing, not only his own playing but in combination with dynamic players such as Max Roach, Roy Haynes, Bud Powell, Fats Navarro, Dizzy Gillespie, and others. Although much more has been written about the harmonic aspects of Bird’s musical language, most of this harmonic conception was already present in the music of pianists and saxophonists from the previous era, before Parker arrived on the scene. Among others, the music of pianists Duke Ellington and Art Tatum, as well as saxophonists Coleman Hawkins and Don Byas,demonstrated an already quite sophisticated grasp of harmony. Just about any recording of Tatum demonstrates a harmonic language that rivaled anything from the musicians of Charlie Parker’s time. Furthermore, one could look at examples such as Coleman Hawkins’ famous 1939 rendition of “Body and Soul” or Don Byas’ 1945 Town Hall duos with Slam Stewart (“I’ve Got Rhythm” and “Indiana”) to see that many of these harmonic aspects were already quite developed. Also in Byas’ recordings, we already see some hint of the rhythmic language that would emerge fully developed in Parker’s playing. |

|

Nach meiner Meinung ist das bei weitem dramatischste Merkmal von Birds musikalischer Sprache der rhythmische Aspekt, insbesondere seine Phrasierung und sein Timing – nicht nur in seinem eigenen Spiel, sondern auch in Verbindung mit dynamischen Musikern wie Max Roach, Roy Haynes, Bud Powell, Fats Navarro, Dizzy Gillespie und anderen. Obgleich viel mehr über die harmonischen Aspekte von Birds musikalischer Sprache geschrieben wurde, so war das meiste dieses harmonischen Konzepts doch bereits in der Musik von Pianisten und Saxofonisten der vorausgegangenen Ära vorhanden, bevor Parker auf der Szene erschien. Die Musik der Pianisten Duke Ellington und Art Tatum, der Saxofonisten Coleman Hawkins und Don Byas und anderer Musiker zeigte bereits ein ziemlich verfeinertes Verständnis von Harmonie. So gut wie jede Aufnahme von Art Tatum zeigt eine harmonische Sprache, die es mit allem der Musiker der Charlie-Parker-Zeit aufnehmen kann. Auch an Beispielen wie Coleman Hawkins berühmter Interpretation von „Body and Soul“ (1939) oder Don Byas Town-Hall-Duos mit Slam Steward aus 1945 (“I’ve Got Rhythm” und “Indiana”) kann man sehen, dass viele dieser harmonischen Aspekte bereits ziemlich entwickelt waren. In Byas‘ Aufnahmen finden wir auch einige Hinweise auf die rhythmische Sprache, die in Parkers Spiel dann voll entwickelt auftritt. |

Not a lot has been written about the rhythmic aspects of this language, and for good reason-there are no words and developed descriptive concepts for it in most Western languages. Western music theory has developed primarily in directions that are great for describing the tonal aspects of music, particularly harmony. However, the language to describe rhythm itself is not very well developed, apart from descriptions of time signatures and other notation-related devices. But over the years, musicians themselves have developed a kind of insider’s language, an informal slang that is helpful to allude to what is already intuited and culturally implied. |

|

Es ist bisher nicht viel über die rhythmischen Aspekte dieser Sprache geschrieben worden – aus gutem Grund, denn es gibt in den meisten westlichen Sprachen keine Worte und entwickelten beschreibenden Konzepte. Die westliche Musik-Theorie hat sich hauptsächlich in Richtungen entwickelt, die großartig im Beschreiben tonaler Aspekte der Musik sind, insbesondere der Harmonik. Die Sprache zur Beschreibung des Rhythmus selbst ist jedoch, abgesehen von der Beschreibung des Takt-Metrums und anderer auf die Notation bezogener Einheiten, nicht sehr gut entwickelt. Im Laufe der Jahre entwickelten die Musiker aber selbst eine Art Insider-Sprache, einen informellen Slang, der hilft, darauf anzuspielen, was kulturell bereits intuitiv bekannt ist und vorausgesetzt wird. |

The implications of Parker’s phrasing helped to catalyze the rhythmic responses that eventually would come from players such as Max Roach, Bud Powell, Fats Navarro, etc. Although the descriptive aspects of these rhythmic concepts are underdeveloped, we could extend our ability to discuss this language by drawing from the perspective of the rhythmic language of the African Diaspora. Dizzy Gillespie referred to Charlie Parker’s rhythmic conception as sanctified rhythms, suggesting a style of playing that was related to music heard in church. Later in this article I will take that analogy a little further when I discuss ternary versus duple time. |

|

Die Implikationen von Parkers Phrasierungsweise halfen, die rhythmischen Antworten, die letztlich von Musikern wie Max Roach, Bud Powell, Fats Navarro usw. kamen, zu katalysieren. Obwohl die beschreibenden Aspekte dieser Konzepte unterentwickelt sind, konnten wir unsere Fähigkeit erweitern, diese Sprache zu diskutieren, indem wir die Perspektive der rhythmischen Sprache der afrikanischen Diaspora heranzogen. Dizzy Gillespie sprach bei Charlie Parkers rhythmischer Konzeption von geheiligten Rhythmen und meinte damit eine Spielweise, die mit jener Musik verwandt ist, die in der Kirche zu hören ist. Später werde ich in diesem Artikel diese Analogie ein wenig weiterführen, wenn ich den ternären Rhythmus gegenüber dem Zweier-Rhythmus diskutiere. |

There is a famous quote by Beethoven that “music is a higher revelation than philosophy.” The tradition of Armstrong, Ellington, Monk, Bird, Von Freeman, Coltrane, etc., has demonstrated to the world the great heights that spontaneous composition can be taken to, and there is great importance in this. Particularly in western cultures, sophisticated spontaneous composition became virtually a lost art, probably only kept alive in the context of the French Organ improvisational schools (Pierre Cochereau, Marcel Dupré, etc.) and some of the various forms of folk music. But the form and approach of the concept of spontaneous composition that was developed in the Armstrong-Parker-Coltrane continuum (to use a phrase coined by Anthony Braxton) and the amount of information that this form of composition projects (both material and spiritual information) is staggering in its scope. This is particularly true when you look at the relatively short amount of time that it has taken for this music to develop. |

|

Es gibt ein berühmtes Zitat von Beethoven, dass „Musik eine höhere Offenbarung als Philosophie ist“. Die Tradition von Armstrong, Ellington, Monk, Bird, Von Freeman, Coltrane usw. hat der Welt die großartigen Höhepunkte gezeigt, auf die die spontane Komposition geführt werden kann, und darin liegt große Bedeutung. Besonders in den westlichen Kulturen wurde die verfeinerte spontane Komposition zu einer nahezu verloren gegangenen Kunst, die vermutlich nur mehr im Kontext der französischen Orgel-Improvisations-Schulen (Pierre Cochereau, Marcel Dupré usw.) und in einigen der verschiedenen Formen von Volksmusik am Leben erhalten wurde. Die Form und die Herangehensweise des Konzepts der spontanen Komposition, das im Armstrong-Parker-Coltrane-Kontinuum (um einen von Anthony Braxton geprägten Ausdruck zu verwenden) entwickelt wurde, und die Menge an Information (sowohl sachlicher als auch spiritueller Information), die diese Form von Komposition auswirft, sind in ihrer Reichweite aber atemberaubend – insbesondere, wenn man die relativ kurze Zeit bedenkt, die die Entwicklung dieser Musik in Anspruch genommen hat. |

That is not to say that other forms of music have not accomplished the same thing in their own way. But this article deals specifically with spontaneous composition as expressed in the music of Charlie Parker. |

|

Das heißt nicht, dass andere Formen von Musik nicht dieselbe Sache auf ihre eigene Weise erreicht haben. In diesem Artikel geht es aber speziell um die spontane Komposition, wie sie in der Musik von Charlie Parker dargestellt wird. |

I will address most of the following performances in some detail with technical analysis, and will mostly concentrate on the rhythmic, melodic and linguistic elements of Parker’s music. |

|

Ich werde die meisten der folgenden Aufnahmen etwas im Detail angehen, mit technischen Analysen, und ich werde mich hauptsächlich auf die rhythmischen, melodischen und linguistischen Elemente der Musik Parkers konzentrieren. |

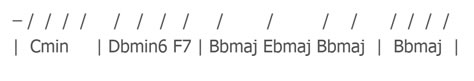

Charlie Parker (Alt-Saxofon), Miles Davis (Trompete), Tadd Dameron (Klavier), Curly Russell (Bass), Max Roach (Schlagzeug); Komposition von Charlie Parker;

aufgenommen am 4. September 1948 im Royal Roost, New York;

Album: Complete Royal Roost Live (Savoy)

This is one of the slickest melodies that I've ever heard. And the manner in which it is played is just sophisticated slang at its highest level. The way the melody weaves back and forth is unreal, and Yard and Max keep this kind of motion going in the spontaneous part of the song. |

|

Das ist eine der [schlüpfrigsten/raffiniertesten] Melodien, die ich jemals gehört habe. Und die Art, wie sie gespielt wird, ist verfeinerter Slang auf höchstem Niveau. Die Art, wie die Melodie auf und ab webt, ist irreal. Und Yard [Yardbird, Bird, Charlie Parker] und Max [Roach] halten diese Art von Bewegung im spontanen Teil des Songs am Laufen. |

I'm a big boxing fan, and I see a lot of similarities between boxing and music. To be more specific, I should say that I see similarities between boxing and music that are done a certain way. There was a point in round eight of the December 8, 2007, Floyd Mayweather, Jr. versus Ricky Hatton fight, starting with an uppercut at 0:44 of this video (2:19 of the round), and also beginning with the check left hook at 2:22 of the video (0:42 of the round) when Floyd was really beginning to open up on Ricky, hitting him with punches coming from different angles in an unpredictable rhythm. If you listen to this fight with headphones on you can almost hear the musicality of the rhythm of the punches. Mayweather was throwing body shots (i.e. punches) and head shots, all coming from different angles: hooks, crosses, straight shots, uppercuts, jabs, an assortment of punches in an unpredictable rhythm. But it's not only that Mayweather's rhythm that was unpredictable, It was also the groove that he got into. |

|

Ich bin ein großer Boxfan und sehe eine Menge Ähnlichkeiten zwischen Boxen und Musik. Um es genauer zu sagen: Ich sehe Ähnlichkeiten zwischen Boxen und Musik, die in einer gewissen Weise gemacht werden. In der 8. Runde des Boxkampfes zwischen Floyd Mayweather jr. und Ricky Hatton am 8. Dezember 2007 gab es einen Punkt (beginnend mit einem Aufwärtsschlag bei 0:44 dieses Videos, 2:19 der Runde, und auch beginnend mit dem linken Haken bei 2:22 des Videos, 0:42 der Runde), wo Floyd begann, Ricky richtig aufzumachen, indem er ihn mit Schlägen aus verschiedenen Winkeln in einem unberechenbaren Rhythmus attackierte. Wenn man diesem Kampf mit Kopfhörern zuhört, kann man geradezu die Musikalität des Rhythmus der Schläge hören. Mayweather teilte Körperschläge und Kopfschläge aus verschiedenen Winkeln aus – Haken, gekreuzte, gerade Schläge, Aufwärtshaken, Gerade, ein Sortiment von Schlägen in einem unberechenbaren Rhythmus. Es war aber nicht nur Mayweathers Rhythmus, der unberechenbar war. Es war auch der Groove, den er hineinbrachte. |

In my opinion, the work of Max Roach in this performance of "Ko-Ko" is very similar to the smooth, fluent, unpredictable groove that elite fighters like Mayweather, Jr., employ. The interplay of Max's drumming with Bird's improvisation sets up a very similar feel to what I saw in Mayweather's rhythm. Near the end of "Ko-Ko," at 2:15, Max does exactly this same kind of boxer motion, accompanying the second half of Miles' interlude improvisation and continuing into Bird's improvisation, only in this case it is like a counterpoint, a conversation in slang between Yard and Max. This is a technique that is both seen and heard throughout the African Diaspora. A certain amount of trickery is involved, a slickness that is demonstrated, for example, by the cross-over dribble and other moves of athletes—for example, the 'ankle-breaking' moves of basketball player Allan Iverson. In addition to this, Max's solo just before the head out is absolutely masterful. Try listening to it at half speed if you can. |

|

Nach meiner Meinung ist die Arbeit von Max Roach in dieser Aufnahme von „Ko-Ko“ sehr ähnlich wie der geschmeidige, flüssige, unberechenbare Groove, den Elitekämpfer wie Mayweather jr. einsetzen. Das Zusammenspiel von Max Schlagzeugspiel mit Birds Improvisation löst ein sehr ähnliches Feeling aus wie das, was ich in Mayweathers Rhythmus sah. Kurz vor dem Ende von „Ko-Ko“, bei 2:15, macht Max genau die gleiche Art von Boxer-Bewegung, während er die zweite Hälfte von Miles Zwischenspiel-Improvisation begleitet und in Birds Improvisation hinein fortfährt. Nur ist sie in diesem Fall wie ein Kontrapunkt, eine Konversation in Slang zwischen Yard und Max. Das ist eine Technik, die in der gesamten afrikanischen Diaspora sowohl gesehen als auch gehört wird. Es ist dabei eine gewisse Menge an Trickserei im Spiel, eine Geschicklichkeit, die sich zum Beispiel im überkreuzten Dribbling und anderen Bewegungen der Athleten zeigt – zum Beispiel in den „knöchelbrecherischen“ Bewegungen des Basketballspielers Allan Iverson. Außerdem ist Maxs Solo unmittelbar vor dem Thema am Ende absolut meisterhaft. Versuch es mit halber Geschwindigkeit zu hören, wenn es dir möglich ist. |

This was the first Charlie Parker recording that I ever heard, as it was the first cut on side A of an album (remember those?) that my father gave me. And I can still vividly remember my response—I had absolutely NO IDEA of what was going on in terms of structure or anything else. It all seemed so esoteric and mysterious to me, as I was previously exposed to the more explicit forms of these rhythmic devices as presented in the popular African-American music that I grew up listening to. Compared to music that I had been listening to when I was younger (before the age of 17), the detailed structures in the music of Parker and his associates were moving so much more quickly, with greater subtlety and on a much more sophisticated level than I was accustomed to. However from the beginning, while listening to this music, I did intuitively get the distinct impression of communication, that the music sounded like conversations. |

|

Das war die erste Charlie-Parker-Platte, die ich hörte. Es war das erste Stück auf der A-Seite eines Albums (erinnert ihr euch daran?), das mein Vater mir gab. Und ich kann mich noch lebhaft an meine Reaktion erinnern – ich hatte absolut KEINE IDEE von dem, was da hinsichtlich Struktur oder sonst etwas vorging. Es erschien mir alles so esoterisch und mysteriös, da ich zuvor den deutlicheren Formen dieser rhythmischen Mittel ausgesetzt war, wie sie in der populären afro-amerikanischen Musik, mit der ich aufwuchs, dargeboten werden. Im Vergleich zu der Musik, die ich gehört hatte, als ich jünger war (vor dem Alter von 17) bewegten sich die detaillierten Strukturen in Parkers Musik und seiner Mitspieler so viel schneller, mit größerer Subtilität und auf einem viel verfeinerteren Niveau als das, an was ich gewöhnt war. Allerdings hatte ich vom Beginn des Hörens dieser Musik an intuitiv den Eindruck der Kommunikation – dass die Musik wie Konversationen klingt. |

In discussing "Ko-Ko," first of all the rhythm of the head is like something from the hood, but on Mars! In the form and movement there is so much hesitation, backpedaling, and stratification. The ever-present phrasing in groups of three and the way the melody shifts in uneven groups, dividing the 32 beats into an unpredictable pattern of 3-3-2-2-3-3-2-2-1-3-4-4. By backpedaling I mean the way that the rhythmic patterns seem to reverse in movement; for example the 8s are broken up as 3-3-2, then as 2-3-3. By hesitation I am referring to the way the next 8 is broken up as 2-2-1-3, as kind of stuttering movement. |

|

Wenn man „Ko-Ko“ bespricht, dann ist zuallererst darauf hinzuweisen, dass das Thema wie etwas aus der Hood [der afro-amerikanischen Community] ist, jedoch auf dem Mars! In der Form und der Bewegung gibt es so viel Verzögerung, Zurückrudern und Schichtung. Sowie die allgegenwärtige Phrasierung in Dreier-Gruppen und die Art, wie sich die Melodie in ungleichen Gruppen verändert, indem sie die 32 Beats in unvorhersehbare Muster von 3-3-2-2-3-3-2-2-1-3-4-4 teilt. Mit Zurückrudern meine ich die Art, wie die rhythmischen Muster in der Bewegung umzukehren scheinen; zum Beispiel werden die 8er aufgebrochen zu 3-3-2 und dann zu 2-3-3. Mit Verzögerung beziehe ich mich auf die Art, wie die nächsten 8 aufgebrochen werden zu 2-2-1-3, zu einer Art stotternden Bewegung. |

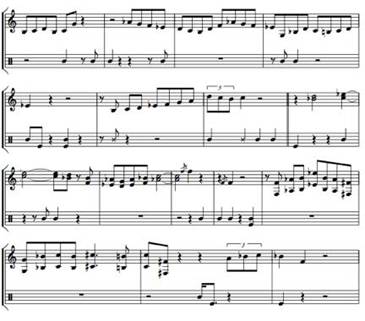

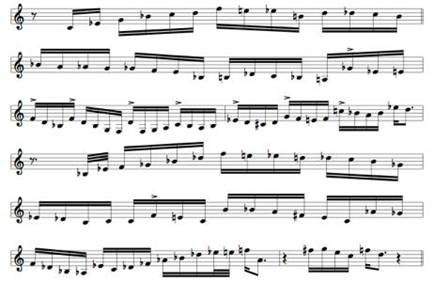

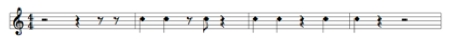

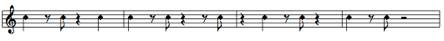

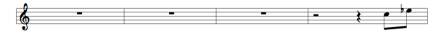

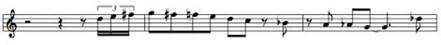

The opening melody of "Ko-Ko": |

|

Die Eröffnungsmelodie von „Ko-Ko“: |

|

|

|

Stratification is just my term for the funky nature of the melody and Max's accompaniment. With this music I always paid more attention to the melody, drums and bass; however, this song form is composed of only melody and drums, with Max's part being spontaneously composed. The way Max scrapes the brushes rhythmically across the snare, frequently pivoting in unpredictable places, adds to the elusiveness and sophistication of this performance. For example, during the head and under Miles' first interlude improvisation (starting at measure 9), Max provides an esoteric commentary, filling in a little more as Parker enters (in measure 17)—however, the beat is always implicit, never directly stated. On this rendition of "Ko-Ko," Bird's temporal sense is so strong that his playing provides the clues for the uninitiated listener to find his/her balance. |

|

Schichtung ist einfach mein Begriff für den funkigen Charakter der Melodie und Maxs Begleitung. Bei dieser Musik achtete ich immer mehr auf die Melodie, das Schlagzeug und den Bass; allerdings besteht diese Form von Song ohnehin nur aus Melodie und Schlagzeug, wobei Maxs Part spontan komponiert ist. Die Art, wie Max die Besen über die Snare-Trommel fetzen lässt und dabei häufig an unvorhersehbaren Stellen schwenkt, verstärkt die Flüchtigkeit und Verfeinerung dieser Darbietung. Zum Beispiel bereitet Max während des Themas und während Miles erster Zwischenspiel-Improvisation (beginnend bei Takt 9) einen esoterischen Kommentar und füllt eine Menge mehr hinein, wenn Parker einsteigt (in Takt 17) – der Beat ist jedoch immer implizit vorhanden, nie direkt ausgedrückt. In dieser Interpretation von „Ko-Ko“ ist Birds Zeitgespür so stark, dass sein Spiel dem uneingeweihten Hörer/der Hörerin die Anhaltspunkte liefert, um seine/ihre Balance zu finden. |

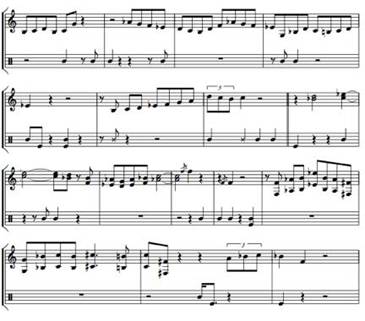

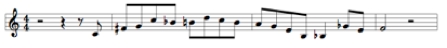

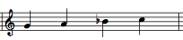

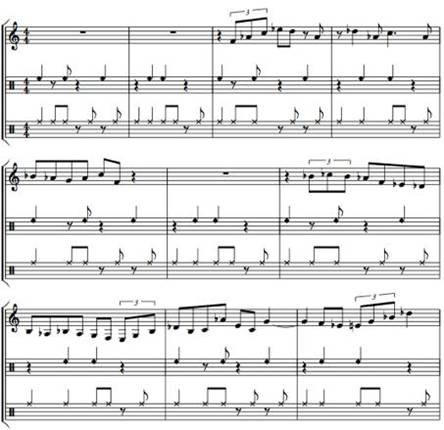

Melody of "Ko-Ko", trumpet, sax, snare & bass drum: |

|

„Ko-Ko“-Melodie, Trompete, Saxofon, Snare- und Bass-Trommel: |

|

|

|

One rarely hears this kind of commentary from drummers, as much of today's music is explicitly stated. The way Max chooses only specific parts of the melody to use as points for his commentary is part of what makes the rhythm so mysterious. Much is hinted at, instead of directly stated. This continues in the spontaneously composed sections of this performance, as Yard plays in a way where there are very hard accents which form an interplay with Max's spacious exclamations. Punches are being mixed here, some hard, some soft, upstairs and downstairs, in ways that form a hard-hitting but unpredictable groove. I've always felt that the obvious speed and virtuosity of this music obscures its more subtle dimensions from many listeners, almost as if only the initiates of some kind of secret order are able to understand it. This kind of slickness and dialog continues throughout this performance, building in ways that ebb and flow just as in a conversation. By the way Miles plays the F in measure 28 early; based on the original 1945 studio recording with Diz and Bird playing the melody, this F should fall on the first beat of measure 29. However, Yard and Max play their parts correctly, so the still developing Miles Davis probably had trouble negotiating this rapid tempo. |

|

Man hört diese Art von Kommentar von Schlagzeugern selten, da viel von der heutigen Musik explizit ausgedrückt wird. Die Art, wie Max nur spezifische Teile der Melodie auswählt, um sie als Ansatzpunkte für seinen Kommentar zu nutzen, ist Teil dessen, was den Rhythmus so mysteriös macht. Vieles ist angedeutet, statt direkt ausgedrückt. Das setzt sich in den spontan komponierten Abschnitten dieser Darbietung fort, wo Yard in einer Weise spielt, bei der es sehr scharfe Akzente gibt, die ein Zusammenspiel mit Maxs großräumigen Ausrufen bilden. Die Schläge sind hier durchmischt, einige harte, einige sanfte, treppauf und treppab, in einer Art und Weise, die einen knallharten, aber unberechenbaren Groove bilden. Ich hab es immer so empfunden, dass die offenkundige Geschwindigkeit und Virtuosität dieser Musik ihre subtileren Dimensionen für viele Hörer verschleiert, fast so, dass nur die Eingeweihten einer Art Geheim-Orden sie verstehen können. Diese Art von Geschicklichkeit und Dialog setzt sich durch die gesamte Darbietung fort und gestaltet in einer Art und Weise, die auf- und abebbt, genau wie in einem Gespräch. Im Übrigen spielt Miles das F in Takt 28 zu früh; ausgehend von der Original-Studio-Aufnahme aus 1945, in der Diz [Dizzy Gillespie] und Bird die Melodie spielten, sollte das F auf den ersten Beat des Taktes 29 fallen. Yard und Max spielen ihre Parts korrekt, sodass der sich noch entwickelnde Miles Davis wahrscheinlich noch Probleme hatte, dieses rasante Tempo zu bewältigen. |

Spontaneously composed music can be analyzed in a similar fashion to counterpoint, in terms of the interaction of the voices. However, it is a counterpoint that has its own rules based on a natural order and intuitive-logic—what esoteric scholar and philosopher Schwaller de Lubicz referred to as Intelligence of the Heart. Also, in my opinion, the cultural DNA of the creators of this music should be taken into account, just as you should take environment and culture into account when studying any human endeavors. Max tends to play in a way that both interjects commentary between Bird's pauses and punctuates Parker's phrases with termination figures. For a drummer to do this effectively he/she must be very familiar with the manner of speaking of the soloist in order to be able to successfully anticipate the varied expressions. |

|

Spontan komponierte Musik kann in einer ähnlichen Weise analysiert werden wie der Kontrapunkt – in Bezug auf die Interaktion der Stimmen. Es ist jedoch ein Kontrapunkt, der seine eigenen Regeln hat, und diese beruhen auf einer natürlichen Ordnung und intuitiven Logik – was der esoterische Gelehrte und Philosoph Schwaller de Lubicz auf die Intelligenz des Herzens bezog. Nach meiner Meinung sollte auch die kulturelle DNA der Schöpfer dieser Musik in Betracht gezogen werden, genauso wie man Umfeld und Kultur berücksichtigt, wenn man irgendwelche menschliche Bestrebungen studiert. Max neigt dazu, in einer Weise zu spielen, die sowohl Kommentare in Birds Pausen einwirft als auch Parkers Phrasen mit Abschlussfiguren unterstreicht. Damit ein(e) Schlagzeuger(in) das effektiv machen kann, muss er/sie sehr vertraut sein mit der Sprechweise des Solisten, um die vielfältigen Äußerungen vorhersehen zu können. |

I have heard many live recordings where it is clear that Max is anticipating Parker's sentence structures and applying the appropriate punctuation. This is not unusual; close friends frequently finish each other's sentences in conversations. With musicians such as Parker and Roach everything is internalized on a reflex level. As this music is rapidly moving sound being created somewhat spontaneously, I believe that the foreground mental activity occurs primarily on the semantic level in the mind, while the internalized, agreed-upon syntactic musical formations may be dealt with by some other more automated process, such as theorized by the concept of the mirror neuron system. What is striking here is the level that the conversations are occurring on—these are very deep subjects! Most of the time, critics and academics discuss this music in terms of individual musical accomplishments, and don't focus enough attention on the interplay. I feel this music first and foremost tells a story. There is definitely a conscious attempt to express the music using a conversational logic. So what I am saying is that while syntax is important, semantics is primary. Too often what the music refers to, or may refer to is ignored. |

|

Ich habe viele Live-Aufnahmen gehört, wo es eindeutig ist, dass Max Parkers Satzstrukturen vorhersieht und die passenden Satzzeichen einsetzt. Das ist nicht ungewöhnlich; enge Freunde beenden häufig die Sätze des jeweils anderen in einem Gespräch. Bei Musikern wie Parker und Roach ist alles auf einer Reflex-Ebene internalisiert. Da diese Musik ein sich rasant bewegender Sound ist, der einigermaßen spontan geschaffen wird, glaube ich, dass die vordergründige mentale Aktivität hauptsächlich auf der semantischen Ebene des Verstandes abläuft, während die internalisierten, vereinbarten syntaktischen musikalischen Formationen von anderen, mehr automatisierten Prozessen gehandhabt werden – etwa jenen, die mit dem Spiegelneuronen-System theoretisch beschrieben werden. Verblüffend ist hier das Niveau, auf dem die Konversationen stattfinden – das sind sehr tiefgründige Subjekte! Die meiste Zeit diskutieren Kritiker und Akademiker diese Musik in Bezug auf individuelle musikalische Leistungen und konzentrieren sich zu wenig auf das Zusammenspiel. Nach meinem Empfinden erzählt diese Musik vor allen Dingen eine Geschichte. Da gibt es definitiv ein bewusstes Bestreben, die Musik unter Verwendung einer Gesprächslogik auszudrücken. Was ich also sage, ist, dass die Syntax zwar wichtig ist, die Semantik [Bedeutung der Zeichen] aber vorrangig ist. Zu oft wird ignoriert, wovon die Musik spricht oder sprechen mag. |

The last half of the bridge going into the last eight before Roach's solo (at 1:32) provides one of these rhythmic voice-leading points where Max goes into his boxing thing, playing some of the funkiest stuff I've heard. Just as instructive are the vocal exclamations of the musicians and possibly some initiated members of the audience, which form additional commentary. There is so much going on in this section that you could write a book about it; an entire world of possibilities is implied, as the rhythmic relationships are far more subtle than what is happening harmonically. |

|

Die letzte Hälfte der Bridge, die in die letzten 8 vor Roachs Solo führt (bei 1:32) liefert einen dieser rhythmischen Stimmführungspunkte, wo Max in diese Boxersache geht, indem er eine der funkigsten Sachen spielt, die ich gehört habe. Aufschlussreich sind auch die vokalen Ausrufe (von Musikern und möglicherweise einiger eingeweihter Mitglieder des Publikums), welche einen zusätzlichen Kommentar bilden. Es ist in diesem Abschnitt so viel los, dass man ein Buch darüber schreiben könnte; eine ganze Welt von Möglichkeiten ist impliziert, da die rhythmischen Beziehungen weit subtiler sind als das, was harmonisch geschieht. |

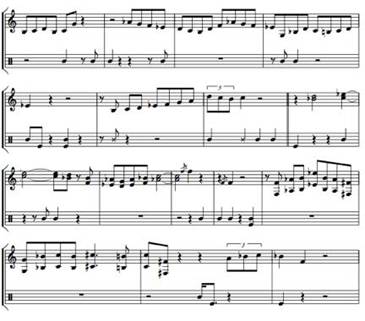

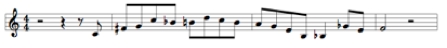

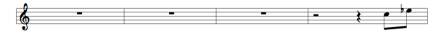

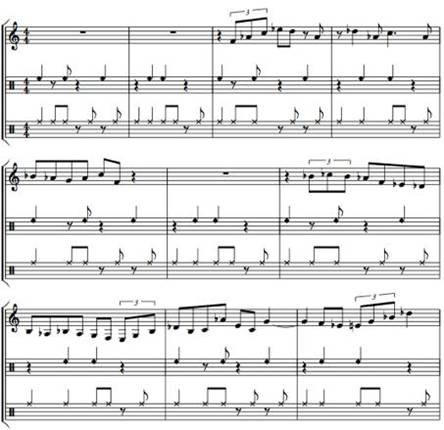

2nd half of last bridge and last 8 of "Ko-Ko", Bird’s solo: |

|

Zweite Hälfte der letzten Bridge und letzte Acht von „Ko-Ko“, Birds Solo: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

This illustrates that on these faster pieces Yard tended to play with bursts of sentences punctuated with shorter internal groupings using hard accents, whereas Max played in a way that effectively demarcated Parker's phrases with longer groupings setting up shifting epitritic patterns*. Max sets these patterns up by repeated figures designed to impress upon the listener a particular rhythmic form, only to suddenly displace the rhythm from what the listener was conditioned to expect. The passage above is a perfect example of this, setting up a hypnotic dance of 2-3-3, only to shift the expected equilibrium with the response of 2-1-3-1-1, then continuing with a slight variation of the initial dance. |

|

Das führt vor Augen, dass Yard in diesen schnelleren Stücken dazu neigte, mit Ausstößen von Sätzen zu spielen, die mit kurzen internen Gruppierungen unter Verwendung scharfer Akzente interpunktiert [mit Satzzeichen versehen] sind, während Max in einer Weise spielte, die Parkers Phrasen mit längeren Gruppierungen, die wechselnde epitritische* Muster aufbauen, effektiv abgrenzt. Max erzeugt diese Muster mit wiederholten Figuren, die dafür ausgelegt sind, beim Hörer den Eindruck von einer speziellen rhythmischen Form hervorzurufen, nur um dann plötzlich die rhythmische Form, die der Hörer zu erwarten konditioniert ist, zu ersetzen. Die oben erwähnte Passage ist ein perfektes Beispiel dafür: Er erzeugt einen hypnotischen Tanz von 2-3-3, nur um das erwartete Gleichgewicht mit der Antwort 2-1-3-1-1 zu ersetzen und dann mit einer geringfügigen Variation des ursprünglichen Tanzes fortzufahren. |

Even the vocal exclamations of the musicians and audience members participates in what I consider to be secular ritualized performances. All of these features that I mention are traits that I consider to be a kind of musical DNA that has been retained from Africa. This music's level of sophistication demanded the intellectual as well as emotional participation of musicians and non-musicians alike (when they could get into the music, which not all people could). The rate of change of each instrument is also instructive. Obviously the soloists are in the foreground playing the instruments that have the swifter motion. In the case of this particular group, the bass would be approximately half the speed of the soloist, with the drums having a mercurial and protean function. In terms of commentaries, the drummer would be the next slowest after the bass and piano, and would be providing the slowest commentary from a rhythmic point of view. However, elements of the drum part are closer to the speed of the soloist. |

|

Sogar die vokalen Ausrufe von Musikern und Mitgliedern des Publikums beteiligen sich an dem, was ich als eine weltliche ritualisierte Darbietung betrachte. All die Eigenschaften, die ich erwähnt habe, sind Charakterzüge, die ich als eine Art musikalische DNA betrachte, die aus Afrika erhalten blieb. Der Verfeinerungsgrad dieser Musik verlangt sowohl die intellektuelle als auch die emotionale Beteiligung der Musiker sowie der Nicht-Musiker (wenn sie in die Musik gelangen können, was nicht alle Leute können). Auch die Änderungsrate eines jeden Instruments ist aufschlussreich. Offensichtlich sind die Solisten im Vordergrund, die jene Instrumente spielen, die die flinkere Bewegung haben. Im Fall dieser speziellen Gruppe bewegt sich der Bass ungefähr mit der halben Geschwindigkeit des Solisten, während das Schlagzeug eine lebhafte und vielgestaltige Funktion hat. In Bezug auf Kommentare ist der Schlagzeuger der nächst langsamste nach Bass und Piano und er liefert den langsamsten Kommentar, aus einem rhythmischen Gesichtspunkt betrachtet. Allerdings sind Elemente des Schlagzeug-Parts näher an der Geschwindigkeit des Solisten. |

*The epitritic ratio is 4 against 3; that is, Max playing the 4 against slow 3 (i.e. a slow pulse which is every 3 measures of 1/1 time). This ratio is used a lot on the continent of Africa. |

|

* Das epitritische Verhältnis ist 4 gegen 3; das heißt, Max spielt die 4 gegen eine langsame 3 (d.h. einen langsamen Puls, der in jedem 3. Takt des 1/1-Taktes schlägt). Dieses Verhältnis wird auf dem afrikanischen Kontinent verwendet. |

Charlie Parker (Alt-Saxofon), Hank Jones (Klavier), Ray Brown (Bass), Buddy Rich (Schlagzeug); Komposition von Charlie Parker; aufgenommen im Oktober 1950 in New York; Album: Bird - The Complete Charlie Parker on Verve

Unlike "Ko-Ko," I included this cut because of the lack of dialog between Parker and Buddy Rich (drums), who plays more of a time-keeping role here. As a result Bird's phrases stand out more against the relief of a less involved backdrop. Here we can concentrate on the question and answer qualities of Parker's playing as well as on the melodic and harmonic content. The harmonic structure of the song is based on one of the standard forms of this time period, Rhythm Changes, derived from the George and Ira Gershwin composition "I Got Rhythm." |

|

Im Gegensatz zu „Ko-Ko“ bezog ich dieses Stück ein wegen dem Mangel an Dialog zwischen Parker und Buddy Rich (Schlagzeug), der hier mehr eine Time-Keeper-Rolle spielt. Infolgedessen heben sich Birds Phrasen mehr gegenüber der Unterstützung durch einen weniger involvierten Hintergrund ab. Wir können uns hier sowohl auf die Frage-und-Antwort-Qualitäten von Parkers Spiel als auch auf den melodischen und harmonischen Inhalt konzentrieren. Die harmonische Struktur des Songs beruht auf einer der Standardformen der damaligen Zeit, den Rhythm Changes, abgeleitet aus George und Ira Gershwins Komposition "I Got Rhythm". |

In my opinion, the main keys to Bird's concept are the movement of the rhythm and melody, with the harmonic concept being fairly simple. Not only has this been communicated to me directly by several major spontaneous composers of that era, but one can find quotes from musicians of this period stating this idea, such as the following from bassist and composer Charles Mingus: |

|

Nach meiner Ansicht sind die Hauptschlüssel zu Birds Konzept die Bewegung des Rhythmus und der Melodie, während das harmonische Konzept recht simpel ist. Das wurde mir nicht nur direkt von mehreren bedeutenden spontanen Komponisten dieser Ära mitgeteilt, sondern man kann auch Zitate von Musikern dieser Periode finden, die diesen Gedanken darlegen, wie das folgende Zitat des Bassisten und Komponisten Charles Mingus: |

“I, myself, came to enjoy the players who didn't only just swing but who invented new rhythmic patterns, along with new melodic concepts. And those people are: Art Tatum, Bud Powell, Max Roach, Sonny Rollins, Lester Young, Dizzy Gillespie and Charles Parker, who is the greatest genius of all to me because he changed the whole era around.” (Liner notes to Let My Children Hear Music) |

|

"Ich hatte selbst Gelegenheit, diese Musiker zu genießen, die nicht einfach nur swingten, sondern neue rhythmische Muster erfanden sowie neue melodische Konzepte. Und diese Leute sind: Art Tatum, Bud Powell, Max Roach, Sonny Rollins, Lester Young, Dizzy Gillespie und Charles Parker, der für mich das größte Genie von allen ist, weil er die ganze Ära veränderte." (Begleittext zur Platte “Let My Children Hear Music “) |

If you have not read these liner notes by Mingus you should really check them out. |

|

Wenn Sie diesen Begleittext von Mingus noch nicht gelesen haben, sollten Sie sich ihn ansehen. |

It is clear that from Mingus' perspective, it is the rhythmic and melodic concepts that are the real innovations of this music. On the one hand, Mingus refers to rhythmic and melodic innovation and sophistication, things that could keep a musician interested from the perspective of the craft of music. At other points in the article Mingus talks about the necessity that the spontaneous compositions be about something, that they tell a story about the lives, experiences and interests of the people performing the songs or of other people, and that these are principles that transcend the craft of music as a thing and move toward the core of what it is to be human. I see Bird's music as fitting squarely within this tradition, whatever name it may be called by. |

|

Es ist eindeutig, dass es aus Mingus Perspektive der Rhythmus und die melodischen Konzepte sind, die die wirklichen Innovationen dieser Musik sind. Einerseits bezieht sich Mingus auf die rhythmischen und melodischen Innovationen und die Verfeinerung [Sophistication], Dinge, die das Interesse eines Musikers aus der Perspektive des Handwerks auf sich ziehen konnten. An anderen Stellen seines Artikels spricht Mingus über die Notwendigkeit, dass die spontanen Kompositionen von etwas handeln sollen, dass sie eine Geschichte über das Leben, die Erfahrungen und Interessen der Leute, die die Songs spielen, oder anderer Leute erzählen sollen und dass dies Prinzipien sind, die das bloße Handwerk der Musik als eine Sache transzendieren und hin zum Kern dessen führen, was es heißt, Mensch zu sein. In meinen Augen fügt sich Birds Musik genau in diese Tradition, die wie auch immer bezeichnet werden mag, ein. |

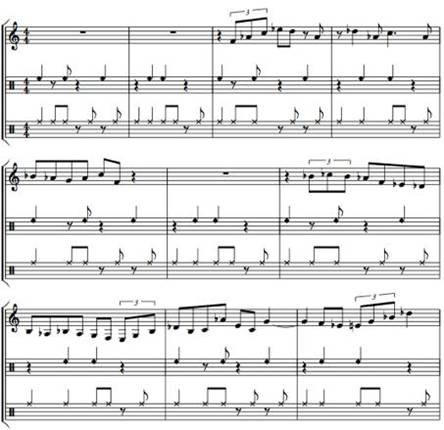

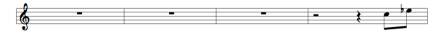

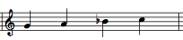

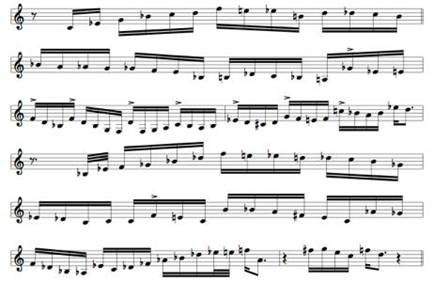

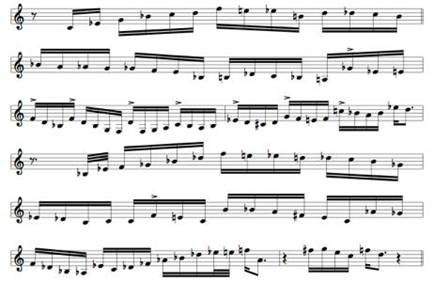

I've always thought of Bird's spontaneous compositions as explanations containing various types of sentence structures. Here, after Buddy Rich's drum introduction, Parker begins "Celebrity" with a 27-beat opening statement, but within this statement is an internal dialog. The harmony and timing help to structure the statement, and gives the listener a sense of the dialog. Generally speaking, what I call dynamic melodic tonalities suggest open ended sentences which are usually (but not always) followed by a response, and in fact lead to or invite a response. |

|

Ich habe Birds spontane Kompositionen immer als Erklärungen verstanden, die verschiedene Typen von Satzstrukturen enthalten. Hier, nach Buddy Richs Schlagzeug-Einleitung, beginnt Parker „Celebrity“ mit einem 27-Beat langen Eröffnungsstatement, aber in diesem Statement ist ein interner Dialog enthalten. Die Harmonie und das Timing helfen, das Statement zu strukturieren, und geben dem Hörer ein Gefühl für den Dialog. Allgemein gesprochen, regt das, was ich dynamische melodische Tonalitäten nenne, Sätze mit offenem Ende an, die üblicherweise (aber nicht immer) eine Antwort nach sich ziehen und sogar zu einer Antwort führen oder dazu einladen. |

Opening (8 beats – static to dynamic)

Response (8 beats – preparation to dynamic)

Elaboration (8 beats – dynamic to static)

Closing (2 beats) |

|

Eröffnung (8 Beats – Statik zu Dynamik)

Antwort (8 Beats – Aufbereitung zu Dynamik)

Ausarbeitung (8 Beats – Dynamik zu Statik)

Abschluss (2 Beats) |

New Opening (8 beats – static to dynamic)

Response (8 beats – preparation to dynamic)

Extension (7.5 beats – dynamic to dynamic)

Semi-Closing (6.5 beats) |

|

Neue Eröffnung (8 Beats – Statik zu Dynamik)

Antwort (8 Beats – Aufbereitung zu Dynamik)

Erweiterung (7.5 Beats – Dynamik zu Statik)

Halb-Abschluss (6.5 Beats) |

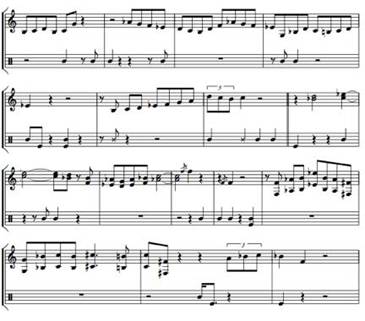

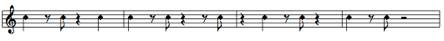

First 16 measure of "Celebrity": |

|

Die ersten 16 Takte von "Celebrity": |

|

|

|

Following up on what Mingus referred to as new melodic concepts, many times musicians use what I call Invisible Paths, meaning that they are not necessarily following the exact path of the composed or accepted harmonic structure for a particular composition, but instead following their own melodic and harmonic roads which functionally perform the same job. The musical description of that job is to form dynamic roads that lead to the same tonal and rhythmic destinations as the composed harmony. This differs slightly from the academic concept of chord substitutions, because these Invisible Paths can be entire alternate roads that are not necessarily related to the composed harmony on a point-by-point basis, and, but nevertheless perform the same function of voice-leading to the cadential points within the music. These paths may be rhythmic, melodic or harmonic in nature; all that is required are the same three elements that are required with a physical path—an origin, a path structure and a destination. |

|

Dem folgend, was Mingus als neue melodische Konzepte bezeichnete, verwenden Musiker oft das, was ich unsichtbare Pfade [Invisible Paths] nenne. Damit meine ich, dass sie nicht notwendigerweise dem exakten Weg der Komposition oder der anerkannten harmonischen Struktur für die jeweilige Komposition folgen, sondern stattdessen ihren eigenen melodischen und harmonischen Straßen folgen, die funktionell denselben Job leisten. Die musikalische Beschreibung dieses Jobs ist, dynamische Straßen zu bilden, die zum selben tonalen und rhythmischen Ziel führen wie die komponierte Harmonie. Dies weicht ein wenig vom akademischen Konzept der Substitutionsakkorde ab, denn diese unsichtbaren Pfade können völlig alternative Straßen sein, die nicht notwendigerweise mit der komponierten Harmonie auf einer Punkt-für-Punkt-Basis verbunden sind und sich widersetzen, als solche gedeutet zu werden. Aber nichtsdestoweniger erfüllen sie innerhalb der Musik dieselbe Funktion der Stimmführung zu den Kadenzpunkten. Diese Pfade können rhythmischer, melodischer oder harmonischer Natur sein; alles, was nötig ist, das sind dieselben drei Elemente, die auch bei einem physischen Pfad erforderlich sind – ein Ausgangspunkt, eine PfadsStruktur und ein Ziel. |

Many older musicians, especially the self-taught musicians with less training in European harmonic theory, have told me that the musicians of that time were primarily thinking in terms of very simple harmonic structures, mostly the four basic triads (major, minor, diminished, augmented) along with some form of dominant seventh chords. Although the harmonic structures were simple, the different ways in which they progressed and were combined were complex, again pointing to the idea that it was the movement of the musical sounds that most concerned these musicians. This is often overlooked by academics who are used to analyzing music by relying on the tool of notation, instead of realizing that music is first and foremost sound, and sound is always in motion. It was in the areas of rhythm and melody where most of the complexity was concentrated. Many of these musicians did not learn music from the standpoint of music notation, so they had a more dynamic concept of the music closely allied with how it sounded rather than how it looked on paper. Unfortunately, for copyright reasons, this website cannot allow me to use sound examples for this article, so, ironically, I will myself be forced to use notation. My choice would be to use geometric symbols and diagrams. However, I would then need to spend a large sections of this article explaining the symbols. |

|

Viele ältere Musiker, speziell die autodidaktischen Musiker mit weniger Ausbildung in europäischer Harmonietheorie, haben mir erzählt, dass die Musiker der damaligen Zeit hauptsächlich in Bezug auf sehr einfache harmonische Strukturen dachten – meistens 4 grundlegende Dreiklänge (Dur, Moll, vermindert, übermäßig) und manche Form von Dominantseptakkord. Auch wenn die harmonischen Strukturen einfach waren, so waren die unterschiedlichen Wege, auf denen sie voranschritten und die kombiniert wurden, doch komplex – wiederum: es war die Bewegung der musikalischen Sounds, das diese Musiker am meisten beschäftigte. Oft übersehen das Akademiker, die gewohnt sind, Musik mithilfe der Werkzeuge der Notation zu analysieren, statt zu realisieren, dass Musik vor allen Dingen Sound ist und Sound immer in Bewegung ist. Es waren die Bereiche des Rhythmus und der Melodie, wo das meiste der Komplexität konzentriert war. Viele dieser Musiker lernten die Musik nicht vom Standpunkt der Notation aus und hatten dadurch ein dynamischeres Konzept von der Musik, das eng damit verbunden war, wie sie klang, statt wie sie auf dem Papier aussah. Leider ist es mir aus urheberrechtlichen Gründen nicht möglich, auf dieser Internetseite Soundbeispiele für diesen Artikel zu verwenden, sodass ich ironischerweise selbst dazu gezwungen bin, die Notation zu verwenden. Ich würde lieber geometrische Symbole und Diagramme verwenden. Dann müsste ich jedoch einen großen Abschnitt dieses Artikels dafür verwenden, die Symbole zu erklären. |

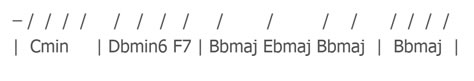

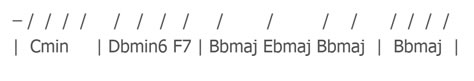

In analyzing these passages, we can sometimes see hybrid structures or harmonic schemes which shift in the course of a melodic sentence. Coming out of Buddy Rich's solo, a simple version of this idea seems to be along the following path, or something similar, for 32 beats. |

|

Beim Analysieren dieser Passagen können wir manchmal hybride Strukturen sehen oder harmonische Anordnungen, die sich im Verlauf eines einzigen melodischen Satzes ändern. Beim Herauskommen aus Buddy Richs Solo scheint eine einfache Version dieser Idee entlang des folgenden Pfades (oder etwas Ähnlichem) über 32 Beats abzulaufen: |

|| Cmin7 F7 | Bb A7 | F7 Dbmin6 | Cmin7 F7 | Fmin7 Bb7 | Ebmaj Ebmin | Bbmaj | C7 F7 || |

|

|| Cmin7 F7 | Bb A7 | F7 Dbmin6 | Cmin7 F7 | Fmin7 Bb7 | Ebmaj Ebmin | Bbmaj | C7 F7 || |

|

|

|

The bridge is even more varied, with Bird’s melodic paths creating their own internal logic, which then resolve back into the logic of the composition. |

|

Die Bridge ist sogar noch variierter, wobei Birds melodische Pfade ihre eigene interne Logik hervorbringen und sich schließlich wieder in der Logik der Komposition auflösen: |

|| Ebmin6 | Amin6 Ebmin6 | Dmin | Fmin6 | Gmin6 (maj7) | Gmin6 | Cmin6 | (F7) || |

|

|| Ebmin6 | Amin6 Ebmin6 | Dmin | Fmin6 | Gmin6 (maj7) | Gmin6 | Cmin6 | (F7) || |

|

|

|

With a little thought, you will notice that these passing tonalities provide the same function as the composed harmonic structure of the song. Notice here that Yard is doing just what he stated in two different versions of the same quotation: |

|

Wenn man ein wenig nachdenkt, wird man bemerken, dass diese durchlaufenden Tonalitäten dieselbe Funktion erfüllen wie die komponierte harmonische Struktur des Songs. Beachte hier, dass Yard genau das macht, was er in zwei unterschiedlichen Versionen desselben Zitates erklärte: |

"I realized by using the high notes of the chords as a melodic line, and by the right harmonic progression, I could play what I heard inside me. That's when I was born." (c. 1939, quoted in Masters of Jazz) |

|

„Als ich die hohen Noten der Akkorde als melodische Linie verwendete und dazu die richtige harmonische Progression spielte, bemerkte ich, dass ich spielen konnte, was ich in mir hörte. Das war es, was mich neu gebar.“ (1939, zitiert in: Masters of Jazz) |

"I found that by using the higher intervals of a chord as a melody line and backing them with appropriately related changes I could play the thing I’d been hearing. I came alive." (1955, Hear Me Talkin' to Ya) |

|

„Ich fand heraus: Wenn ich die höheren Intervalle eines Akkords als Melodielinie verwendete und sie mit den passenden zugehörigen Changes begleitete, dann konnte ich die Sache spielen, die ich gehört hatte. Ich wurde lebendig.“ (1955, zitiert in: Hear Me Talkin' to Ya) |

However, Parker's version of higher intervals of a chord was not in the form of flatted 9ths, 11ths and 13ths, but in the form of simple melodic and triadic structures that reside at a higher location within the tonal gamut which I refer to as the Matrix (who really knows how Bird thought of it?). In this case, simple minor structures such as Ebmin6, Amin6 and Fmin6 are the upper intervals of Ab7, D7 and Bb7, respectively. These minor triads with an added major sixth are very important structures in music, often mistakenly called half-diminished (for example Amin6 could be called F# half-diminished today). In this instance, the function of Amin6 is that of dynamic A minor, in the same sense that the function of D7 is that of dynamic D major. By dynamic I mean energized with the potential for change. Adding a major 6th to a minor triad has a similar (but reciprocal) function to adding a minor 7th to a major triad, and that function in many cases is to energize the triad, to infuse it with a greater potential for change, due to the perceived unstable nature of the tritone interval. Pianist Thelonious Monk was a master of this technique, and demonstrated this to many of the other musicians of this time (including Dizzy and Bird). Regarding whether to use the name half-diminished or minor triad with the added 6th, this is a case where a simple change in name can obscure the melodic and harmonic function of a particular sound. Dizzy Gillespie mentions this in his autobiography when he says that for him and his colleagues, there was no such thing as half-diminished chords; what is called a half-diminished chord today, they called a minor triad with a major sixth in the bass. |

|

Wie auch immer, Parkers Version der höheren Intervalle eines Akkords war nicht in der Form von flatted 9ths, 11ths und 13ths, sondern in der Form einfacher melodischer Strukturen und Dreiklang-Strukturen, die in einer höheren Lage innerhalb der tonalen Skala liegen, welche ich als Matrix bezeichne (wer weiß wirklich, wie Bird darüber dachte?). In diesem Fall sind einfache Moll-Strukturen wie Eb-Moll-6, A-Moll-6 und F-Moll-6 die höheren Intervalle von jeweils Ab7, D7 und Bb7. Diese Moll-Dreiklänge mit einer zusätzlichen Dur-Sexte sind sehr wichtige Strukturen in der Musik, die oft fälschlicherweise halb-vermindert genannt werden (zum Beispiel wird A-Moll-6 heute manchmal als F# halb-vermindert bezeichnet). In diesem Fall ist die Funktion von A-Moll-6 die eines dynamischen A-Moll, im selben Sinn, wie die Funktion von D7 die eines dynamischen D-Dur ist. Mit „dynamisch" meine ich aufgeladen mit dem Potential für Veränderung. Eine Dur-Sexte zu einem Moll-Dreiklang hinzuzufügen, hat eine ähnliche (aber reziproke) Funktion wie das Hinzufügen einer Moll-Septime zu einem Dur-Dreiklang und diese Funktion ist in vielen Fällen, den Dreiklang aufzuladen, ihn mit einem größeren Potential für Veränderung anzufüllen – aufgrund des gefühlten unstabilen Wesens des Tritonus-Intervalls. Der Pianist Thelonious Monk war ein Meister dieser Technik und führte das vielen anderen Musikern der damaligen Zeit (einschließlich Dizzy und Bird) vor. Zur Frage, ob man die Bezeichnungen „halb-vermindert“ oder „Moll-Dreiklang mit zusätzlicher Sexte“ verwendet: Das ist ein Fall, in dem die bloße Veränderung der Bezeichnung die melodische und harmonische Funktion eines speziellen Sounds vernebeln kann. Dizzy Gillespie erwähnt das in seiner Autobiographie, wo er sagt, dass es für ihn und seine Kollegen nicht so etwas wie halb-verminderte Akkorde gab; was heute ein halb-verminderter Akkord genannt wird, nannten sie einen Moll-Dreiklang mit einer Dur-Sexte im Bass. |

"Monk doesn't actually know what I showed him. But I do know some of the things he showed me. Like, the minor-sixth chord with a sixth in the bass. I first heard Monk play that. It's demonstrated in some of my music like the melody of "Woody 'n You," the introduction to "Round Midnight," and a part of the bridge to "Mantaca.".... There were lots of places where I used that progression... and the first time I heard that, Monk showed it to me, and he called it a minor-sixth chord with a sixth in the bass. Nowadays, they don't call it that. They call the sixth in the bass, the tonic, and the chord a C-minor seventh, flat five. What Monk called an E-Flat-minor sixth chord with a sixth in the bass, the guys nowadays call a C-minor seventh flat five... So they're exactly the same thing. An E-Flat-minor chord with a sixth in the bass is C, E-flat, G-flat, and B-flat. C-minor seventh flat five is the same thing, C, E-flat, G-flat, and B-flat. Some people call it a half diminished, sometimes." (from the chapter "Minton's Playhouse" in To Be or Not To Bop) |

|

„Monk wusste in Wirklichkeit nicht mehr, was ich ihm gezeigt hatte. Aber ich weiß noch einiges, was er mir gezeigt hat, zum Beispiel den Moll-Sext-Akkord mit einer Sexte im Bass. Das habe ich zuerst von ihm gehört. Es kommt in meiner Musik einige Male vor, zum Beispiel in Woody 'n You, in der Einleitung von Round Midnight und in einem Teil der Bridge von Manteca. … Es gab eine Menge Stellen, wo ich diese Progression verwendete … und das erste Mal, dass ich das hörte, war, als Monk mir das zeigte, und er nannte es einen Moll-Sext-Akkord mit einer Sexte im Bass. Heutzutage nennen sie das anders: Sie nennen die Sexte im Bass die Tonika und den Akkord einen C-Moll-7-Akkord mit verminderter Quinte. Was Monk einen Es-Moll-Sext-Akkord mit der Sexte im Bass nannte, nennen die Typen heute einen C-Moll-7-Akkord mit verminderter Quinte … Also ist es genau das gleiche. Ein Es-Moll-Akkord mit einer Sexte im Bass besteht aus C, Es, Ges und B. C-Moll-7 mit verminderter Quinte ist dasselbe wie C, Es, Ges und B. Manche Leute nennen es manchmal halb-vermindert.“ (aus dem Kapitel „Mintons Playhouse“, in: To Be or Not To Bop) |

Charlie Parker (Alt-Saxofon), Miles Davis (Trompete), John Lewis (Klavier), Curly Russell (Bass), Max Roach (Schlagzeug); Komposition von Charlie Parker; aufgenommen am 24. September 1948 in New York; Album: Complete Savoy & Dial Studio Sessions

This composition is another example of the many linguistic rhythmic devices Parker used in his music that are not much discussed. In my opinion, the composed melody is clearly an explanation with variations. The opening phrase of the melody is an explanation of some kind, followed by "but perhaps" (going into measure 5), which begins the first alternate explanation. Then "perhaps" (into measure 7) begins a second alternate explanation. "Perhaps" (into measure 9) begins the final clarification, then the melody ends with the responses in measures 11 and 12—"perhaps, perhaps, perhaps". Therefore we can think of the melodic segments in between the "perhaps" as some sort of discussion and clarification of a particular situation, lending more evidence to the literal admonishment of the cats to "always tell a story" with your music. Obviously in this song there is an added onomatopoetic dimension to the melody that allowed me to at least recognize the perhaps musical phrase at an early stage in my career when I knew very little about the structure of music. But this more obvious example also served notice to me that these possibilities existed within this music, and just maybe there also were elements of the spontaneous compositions that exhibited these features. |

|

Diese Komposition ist ein weiteres Beispiel für die vielen linguistischen rhythmischen Bauteile, die Parker in seiner Musik verwendete und die wenig diskutiert werden. Nach meiner Auffassung ist die komponierte Melodie eindeutig eine Erklärung mit Variationen. Die Eröffnungsphrase der Melodie ist eine Art Erklärung, gefolgt von „but perhaps“ [aber vielleicht] (beim Übergang in Takt 5), welches die erste alternative Erklärung startet. Dann startet „perhaps“ (in Takt 7 hinein) eine zweite alternative Erklärung. „Perhaps“ (in den Takt 9 hinein) startet die endgültige Aufklärung und dann endet die Melodie in den Takten 11 und 12 mit den Antworten: „perhaps, perhaps, perhaps“. Wir können die melodischen Abschnitte zwischen den „Perhaps“ somit als eine Art Diskussion und Aufklärung einer bestimmten Situation verstehen, was der buchstäblichen Aufforderung der Meister, mit seiner Musik „immer eine Geschichte zu erzählen“, verstärkte Beweiskraft verleiht. In diesem Song wird der Melodie offensichtlich eine lautmalerische Dimension hinzugefügt, die mir immerhin ermöglichte, die musikalische „Perhaps“-Phrase in einem frühen Stadium meiner Karriere, als ich noch sehr wenig über die Struktur der Musik wusste, zu erkennen. Dieses besonders offensichtliche Beispiel ließ mich aber auch erkennen, dass diese Möglichkeiten innerhalb der Musik bestehen und es möglicherweise auch Elemente der spontanen Kompositionen gab, die diese Eigenschaften aufweisen. |

This was my intuitive reaction to this song when I first heard it in my formative years as I was still learning how to play, and it is still how I understand it when I listen today. But beyond the more obvious example of this composed melody, I feel that the spontaneous part of this composition, indeed of all of Parker's compositions, are also explanations, and that they are all telling stories. And as mentioned before, they contain the same kinds of exclamations, dialog, linguistic phraseology, and common sense structure that is contained in everyday conversation, with the exception that this linguistic structure is based on the sub-culture of the African-American community of that time, what most people would call slang. This is particularly evident in the rhythm of the musical phrases. The way Max answers the melody is definitely conversational. I hear the same kinds of rhythms that I see when watching certain boxers, basketball players, dancers, and the timing of most of the various activities that go on in the hood. However, this same rhythmic sensibility can occur on various levels of sophistication, and with the music of Bird and his cohorts, it occurs on an extremely sophisticated artistic level. |

|

Das war meine intuitive Reaktion auf diesen Song, als ich ihn zum ersten Mal hörte und ich in meinen Entwicklungsjahren war, in denen ich noch zu spielen lernte – und ich verstehe ihn noch heute so, wenn ich ihn mir anhöre. Abgesehen von diesem besonders offensichtlichen Beispiel dieser komponierten Melodie glaube ich jedoch, dass auch der spontane Teil dieser Komposition – sowie auch aller anderen Kompositionen Parkers – Erklärungen sind und dass sie alle Geschichten erzählen. Und sie enthalten, wie bereits erwähnt, dieselben Arten der Ausrufe, des Dialogs, der linguistischen Ausdrucksweise und der Struktur des Alltagsverstandes, wie sie in der Alltagskonversation enthalten sind, mit der Besonderheit, dass diese linguistische Struktur auf der Subkultur der afro-amerikanischen Community der damaligen Zeit beruht, die die meisten Leute „Slang“ nennen. Das ist besonders in den Rhythmen der musikalischen Phrasen evident. Die Art, wie Max der Melodie antwortet, ist definitiv gesprächsartig. Ich höre dieselben Arten von Rhythmen, die ich beim Beobachten von Boxern, Basketballspielern, Tänzern und des Timings der meisten der verschiedenen Aktivitäten, die in der Hood [Neighborhood, afro-amerikanische Nachbarschaft] ablaufen, sehe. Dieselbe rhythmische Sensibilität kann jedoch in unterschiedlichen Graden der Verfeinerung [Sophistication] auftreten und in der Musik von Bird und seiner Kollegen tritt sie auf einem extrem verfeinerten künstlerischen Niveau auf. |

This subject of musical conversation brings up the issue of African-Diapora DNA. Scholar Schwaller de Lubicz made reference to a theory that the ancient Egyptians, at some very early point in their existence, had a language whose structure and utterances consisted of pure modulated tones similar to music, as opposed to the phonetic languages of today. Given that their ancient writing contained no symbols for vowels, this idea may seem far-fetched. However, because the recorded writing of this civilization documents over two millennia, a great deal of change must have occurred within the language. |

|

Dieses Thema der musikalischen Konversation bringt das Thema der afrikanischen Diaspora-DNA ins Spiel. Der Gelehrte Schwaller de Lubicz nahm Bezug auf eine Theorie, nach der die alten Ägypter an einem sehr frühen Punkt ihrer Existenz eine Sprache hatten, deren Struktur und Äußerungen aus puren modulierten Tönen bestanden, ähnlich wie Musik – im Gegensatz zu den phonetischen Sprachen von heute. Angesichts der Tatsache, dass ihre alte Schrift keine Symbole für Selbstlaute enthielt, mag diese Idee als weit hergeholt erscheinen. Es muss jedoch – weil die erfasste Schrift dieser Zivilisation es über zwei Jahrtausende belegt – eine große Menge an Veränderung innerhalb der Sprache erfolgt sein. |

Many modern linguists believe somewhat the opposite, that the original human languages contained clicks or were predominantly click languages. These linguists use the languages of the Hadza people of Tanzania and Jul'hoan people of Botswana as evidence. However, the evidence of drum languages in the Niger-Congo region of Sub-Saharan Africa tells another story. For example, the drum languages of the Yoruba of Nigeria, Ghana, Togo and Benin; the Ewe of Ghana, Togo and Benin; the Akan of Ghana; and the Dagomba of northern Ghana, still exist today. In the languages of these areas, register tone languages are common, where pitch is used to distinguish words (as opposed to contour, as in Chinese). Since many of these West-African languages are tonal, suprasegmental communication is possible through purely prosodic means (i.e. rhythm, stress and intonation). There is little doubt that emotional prosody (sounds that represent pleasure, surprise, anger, happiness, sadness, etc.) predated the modern concept of languages. If the early ancient Egyptians developed a highly structured form of suprasegmental communication, it is quite possible that de Lubicz' theory is correct. In any case, there is plenty of precedent for the exclusive use of tones as language. |

|

Viele moderne Linguisten glauben mehr oder weniger das Gegenteil: dass die ursprünglichen menschlichen Sprachen Schnalzlaute enthielten oder überwiegend Schnalzlaut-Sprachen waren. Diese Linguisten führen die Sprachen des Hazda-Volkes in Tansania und des Jul'hoan-Volkes in Botswana als Beleg an. Die Evidenz der Trommelsprachen in der Niger-Kongo-Region im Sub-Sahara-Afrika erzählt jedoch eine andere Geschichte. Zum Beispiel existieren bis heute die Trommel-Sprachen der Yoruba in Nigeria, Ghana, Togo und Benin; der Ewe in Ghana, Togo und Benin; der Akan in Ghana; und der Dagomba im nördlichen Ghana. In diesen Gegenden sind Tonsprachen gebräuchlich, in denen die Tonhöhe zur Unterscheidung von Worten verwendet wird (im Gegensatz zur Kontur, wie im Chinesischen). Da viele dieser west-afrikanischen Sprachen tonal sind, ist die suprasegmentale Kommunikation mithilfe bloßer prosodischer Mittel (d.h. Rhythmus, Betonung und Intonation) möglich. Es bestehen kaum Zweifel daran, dass emotionale Prosodie (Laute, die Freude, Überraschung, Ärger, Fröhlichkeit, Traurigkeit usw. ausdrücken) dem modernen Konzept der Sprachen vorausging. Wenn die frühen alten Ägypter eine hochgradig strukturierte Form einer suprasegmentalen Kommunikation entwickelt haben, ist es durchaus möglich, dass die Theorie von de Lubicz stimmt. Auf jeden Fall gibt es viele Beispiele für die ausschließliche Verwendung von Tönen als Sprache. |

Regarding the sections containing spontaneous composition, of course, many musical devices are involved, rhythmic, melodic, harmonic and formal, all on a very high level. Which is why most students of this music are absorbed in the musical parameters—there is so much there. But I propose that much of what is being accomplished musically can be seen more clearly if we take into account the perspective of the African-Diaspora, rather than have discussions primarily about harmonic structure, etc. Many of the rhythms that Parker uses are not merely related to African music in the linguistic sense that I have outlined above, nor only related to the notion of having a certain kind of swing or groove. Also many of the structural rhythmic tendencies of the Diaspora have been retained within African-American culture. |

|

Was die Bereiche anbelangt, die die spontane Komposition umfassen, so sind natürlich viele musikalische Bauelemente involviert: rhythmische, melodische, harmonische und formale, alle auf einem sehr hohen Niveau. Deshalb werden die meisten Studenten dieser Musik gänzlich von den musikalischen Parametern in Anspruch genommen – es gibt da so viel. Ich behaupte jedoch, dass viel von dem, was musikalisch ausgeführt wird, klarer gesehen werden kann, wenn wir die Perspektive der afrikanischen Diaspora berücksichtigen, anstatt hauptsächlich über harmonische Strukturen usw. zu diskutieren. Viele der Rhythmen, die Parker verwendete, sind nicht bloß im linguistischen Sinn, den ich oben skizziert habe, mit afrikanischer Musik verwandt, auch nicht bloß durch die Vorstellung von einem gewissen Swing oder Groove: Auch viele der strukturellen rhythmischen Tendenzen der Diaspora sind innerhalb der afro-amerikanischen Kultur bewahrt worden. |

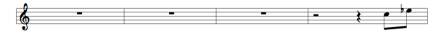

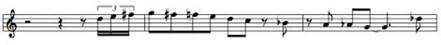

We can start by looking at the concept of clave in Parker's playing. The phrase at 0:26 of take 1 is precisely the kind of slick musical sentence that Parker was renowned for among his peers. I feel that the emphasis in the phrasing contains rhythmic figures very similar to various clave patterns. This phrase is repeated almost verbatim at 0:55 with the addition of a turn and a slight shift in the clave pattern: |

|

Wir können beginnen, indem wir uns das Konzept der Clave in Parkers Spiel ansehen. Die Phrase bei 0:26 des Take 1 ist genau die Art von raffiniertem musikalischem Satz, für die Parker unter seinen Kollegen bekannt war. Nach meinem Empfinden enthält die Betonung in der Phrasierung rhythmische Figuren, die sehr ähnlich wie verschiedene Clave-Muster sind. Diese Phrase wird fast wortwörtlich bei 0:55 wiederholt mit einer zusätzlichen Wendung und einer geringfügigen Veränderung im Clave-Muster: |

|

|

|

(at 0:26): |

|

(bei 0:26): |

|

|

|

versus: |

|

versus: |

|

|

|

(at 0:55): |

|

(bei 0:55): |

|

|

|

Of course, you need to listen to the recording to get a feel for the emphasis, but my point here is that there does not seem to be much discussion of this aspect of Bird's internal sense of rhythmic structure. Recognition of a sense of clave in Parker's playing is a key (pardon my pun) to beginning to investigate his complex rhythmic concepts in greater detail. It would be instructive to listen to Bird's spontaneous compositions only for their rhythmic content without regard for the pitches. Then it would be revealed that many of his phrases contain the same kinds of rhythmic structures found in the phrasing of the master drummers of West Africa, with the exception of the pitch conception. An investigation of the starting and ending points of Parker's phrases reveals a kinship to these Sub-Saharan drum masters. |

|

Man muss natürlich die Aufnahme selbst anhören, um ein Gefühl für die Betonung zu bekommen. Mein Argument ist hier jedoch, dass es nicht viel Diskussion zu diesem Aspekt von Birds internem Sinn für rhythmische Struktur gibt. Das Erkennen eines Sinnes für die Clave in Parkers Spiel ist ein Schlüssel (entschuldigen Sie mein Wortspiel [Clave: spanisch Schlüssel]) zur detaillierteren Untersuchung seines komplexen rhythmischen Konzepts. Es ist aufschlussreich, Birds spontane Kompositionen nur hinsichtlich ihres rhythmischen Inhalts, ohne Beachtung der Tonhöhen, anzuhören. Dann wird offensichtlich, dass viele seiner Phrasen dieselbe Art rhythmischer Strukturen enthalten, die in der Phrasierung der Meistertrommler West-Afrikas zu finden sind – mit Ausnahme der Tonhöhenkonzeption. Eine Untersuchung der Start- und Endpunkte von Parkers Phrasen offenbaren eine Verwandtschaft zu diesen Sub-Sahara-Trommelmeistern. |

Take as an example this melodic sentence at 0:38 of take 1 of "Perhaps": |

|

Siehe zum Beispiel diesen melodischen Satz bei 0:38 des Take 1 von "Perhaps": |

|

|

|

There are several rhythmic shifts of emphasis here that suggest a compressing and lengthening of phrases. Starting on beat 3 of measure 2, the shift in emphasis within the phrase suggests groupings of 6-4-5-3-4 (in quarter note pulses). This concept is similar to the classic mop-mop figure; i.e. 4-3-5-4, and is one of the hallmarks of Bird's spontaneous compositions. |

|

Es gibt hier etliche rhythmische Verschiebungen der Betonung, die den Eindruck einer Verdichtung und Verlängerung der Phrasen vermitteln. Die beim Beat 3 des Taktes 2 beginnende Verschiebung der Betonung innerhalb der Phrase deutet eine Gruppierung in 6-4-5-3-4 an (in einem Viertelnotenpuls). Dieses Konzept ist ähnlich wie die klassische Mop-Mop-Figur, d.h. 4-3-5-4, und ist eines der Kennzeichen von Birds spontanen Kompositionen. |

Charlie Parker (Alt-Saxofon), Miles Davis (Trompete), Duke Jordan oder Al Haig (Klavier), Tommy Potter (Bass), Max Roach (Schlagzeug); Komposition von Thelonious Monk; aufgenommen im Juli 1948 in New York; Album: The Complete Benedetti Recordings of Charlie Parker (Mosaic)

These various performances of Parker, recorded by saxophonist Dean Benedetti, demonstrate the combination of looseness and tightness of this particular band, which I consider Bird's most effective working band. I heard about these recordings before I knew they physically existed, and I even heard a few of them long before this box set came out, so it was a real pleasure to finally hear the entire collection. For economic reasons, Benedetti usually only recorded the solos of Parker and not the other musicians, so these recordings are quite fragmented. Furthermore the sound quality is frequently poor; these are not recordings that audiophiles will be writing home about. However, for musicians studying this music, this collection is a goldmine. I compare it to finding a new ancient tomb in the Valley of the Kings in Egypt, in terms of the musical treasures it yields. |

|

Die verschiedenen Auftritte von Parker, die der Saxofonist Dean Benedetti aufnahm, demonstrieren die Kombination von Lockerheit und Festigkeit dieser speziellen Band, welche ich als Birds effektivste Working-Band betrachte. Ich hörte von diesen Aufnahmen, bevor mir bekannt wurde, dass sie tatsächlich existieren, und ich hörte sogar einige von ihnen, bevor dieses Box-Set herauskam. Daher war es ein echtes Vergnügen, schließlich die gesamte Sammlung zu hören. Aus ökonomischen Gründen nahm Benedetti gewöhnlich nur die Soli von Parker auf und nicht die der anderen Musiker, sodass diese Aufnahmen ziemlich bruchstückhaft sind. Außerdem ist die Klangqualität häufig schlecht. Das sind keine Aufnahmen, an denen Audiophile Gefallen finden. Für Musiker, die diese Musik studieren, ist diese Sammlung jedoch eine Goldmine. Ich vergleiche sie mit dem Finden eines neuen antiken Grabs im Tal der Könige in Ägypten, in Bezug auf die musikalischen Schätze, die sie liefert. |

Example A: 52nd Street Theme #275 |

|

Beispiel A: 52nd Street Theme #275 |

This version of Monk's composition was usually played as a break tune, a signal that the set is coming to a close. This take is really just a fragment (similar to a find in an archeological dig), but man, it swings hard! When Parker's sax solo enters after he speaks to the audience, the band settles into a serious groove, everybody responds to Yard, and the beat lays back to the extreme, giving the impression that the band is slowing down. |

|

Diese Version von Monks Komposition wurde üblicherweise als eine Pausen-Melodie gespielt, als ein Signal dafür, dass der Set demnächst endet. Dieser Take ist wirklich bloß ein Fragment (ähnlich wie ein Fund bei einer archäologischen Ausgrabung), aber Mann, swingt das hart! Wenn Parkers Sax-Solo beginnt, nachdem er zum Publikum sprach, legt sich die Band in einen massiven Groove. Jeder antwortet Yard, der Beat ist extrem zurückgelehnt und vermittelt den Eindruck, dass die Band langsamer wird. |

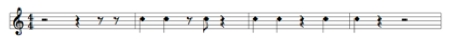

Bird’s solo on "52nd Street Theme #275": |

|

Birds Solo in "52nd Street Theme #275": |

|

|

|

It's clear that this groove emotionally hits those who are present, as can be heard by the various exclamations. This reaction from the people is what I love about live recordings in general—at least recordings done in the presence of responsive audiences. The steady rhythm of the rising spontaneous melody that Yard plays in the opening eight measures creates tension and is perfectly offset by the snaking melody of the second eight, with its dancing, shifting, clave-like patterns that begin in the 11th measure (at 0:42): |

|

Es ist offensichtlich, dass dieser Groove die Anwesenden emotional trifft, wie an den verschiedenen Ausrufen zu hören ist. Diese Reaktion von den Leuten liebe ich allgemein an Live-Aufnahmen – zumindest bei Aufnahmen, die vor einem antwortenden Publikum gemacht wurden. Der stete Rhythmus der aufsteigenden spontanen Melodie, die Yard in den eröffnenden 8 Takten spielt, erzeugt Spannung und wird perfekt von der schlängelnden Melodie der zweiten Acht ausgeglichen, mit ihren tanzenden, verschiebenden, Clave-artigen Mustern, die im 11. Takt (bei 0:42) beginnen: |

Rhythm of the clave-like pattern at measure 11 of "52nd Street Theme #275": |

|

Rhythmus des Clave-artigen Musters bei Takt 11 von "52nd Street Theme #275": |

|

|

|

Again, this demonstrates the use of rhythms that reveal elements retained from West-African concepts. |

|

Das demonstriert wiederum die Verwendung von Rhythmen, die Elemente zeigen, die von west-afrikanischen Konzepten erhalten blieben. |

Example B: 52nd Street Theme #238 |

|

Beispiel B: 52nd Street Theme #238 |

This version is also very dynamic. I love the space that Bird utilizes in this very loose version. Right from the beginning, when Parker plays the augmentation of the melody, we know that he is on top of his game. He does not even bother to complete the melody, immediately launching into a spontaneous statement. The bridge is beautiful! Obviously Parker meant to play the melody here, but stumbles a little. But he sounds like Michael Jordan here, if you follow what I mean, by adjusting in midstream and turning his misstep into a beautiful melodic statement where antecedent and consequent are both preceded by the same rhythmic misstep (mm 1 and 5 below), which transform the original stutter into part of the form of the statement. As with many of Bird's conversations, the form of the statement is irregular but makes perfect rhythmic sense in terms of balance, one of the traits that distinguishes him from most of his musical colleagues. Also the many alternate tonal paths and delayed resolutions (6th, 7th and 9th measures of bridge) add to the hipness of the statement. |

|

Diese Version ist ebenfalls sehr dynamisch. Ich liebe den freien Raum, den Bird in dieser sehr lockeren Version nutzt. Sofort von Beginn an, wo Parker die Augmentation der Melodie spielt, ist offensichtlich, dass er auf der Spitze seines Spiels ist. Er macht sich nicht einmal die Mühe, die Melodie zu Ende zu führen, sondern legt sofort mit seinem spontanen Statement los. Die Bridge ist wunderschön! Offensichtlich beabsichtigte Parker hier, die Melodie zu spielen, strauchelt aber ein wenig. Er klingt hier jedoch wie Michael Jordan, wenn man meinen Gedanken folgt: Er korrigiert in der Strommitte und wendet seinen Fehltritt in ein schönes melodisches Statement, wo sowohl dem Vordersatz als auch dem Nachsatz derselbe rhythmische Fehltritt vorangestellt wird [(mm 1 and 5 below)], was das ursprüngliche Straucheln zu einem Teil der Form des Statements verwandelt. So wie bei vielen von Birds Konversationen ist die Form des Statements unregelmäßig, macht jedoch im Sinne der Balance in rhythmischer Hinsicht absolut Sinn – eines der Merkmale, die ihn von den meisten seiner Musikerkollegen unterscheiden. Auch die vielen alternativen tonalen Pfade und hinausgezögerten Auflösungen (6., 7. und 9. Takt der Bridge) verstärken die Hipness des Statements. |

Bridge: 2-beat stutter – 6-beat antecedent, 3-beat stutter – 18 beat consequent of "52nd Street Theme #238": |

|

Bridge: 2-Beat-Straucheln – 6-Beat-Vordersatz, 3-Beat-Straucheln – 18 Beat-Nachsatz von "52nd Street Theme #238": |

|

|

|

Starting from the second eight of the first chorus of the solo we hear the kind of smooth melodic voice-leading that Parker popularized in this music. |

|

Beginnend bei den zweiten Acht des ersten Chorus des Solos hören wir die Art von geschmeidiger melodischer Stimmführung, die Parker in dieser Musik bekannt gemacht hat. |

2nd eight, Bridge and last eight of "52nd Street Theme #238": |

|

Zweite Acht, Bridge und letzte Acht von "52nd Street Theme #238": |

|

|

|